The following ran as a special report in the January 2016 newsletter of Mark Anderson’s Strategic News Service. I post it now, as the right's hate-all-government narrative hits hysteric-histrionic levels. Rep. Mick Mulvaney, recently selected as Trump's director of the Office of Management and Budget, posted “Do we really need government-funded research at all?” Which makes this an existential threat to your lives, and mine.

Does government-funded science play a role in stimulating innovation?

By David Brin

The hypnotic incantation that all-government-is-evil-all-the-timewould have bemused and appalled our parents in the Greatest Generation – those who persevered to overcome the Depression and Hitler, then contained Stalinism, went to the moon, developed successful companies and built a mighty middle class, all with powerful unions and at high tax rates.

The mixed society that they built emphasized a wide stance, pragmatically stirring private enterprise with targeted collective actions, funded by a consensus negotiation process called politics. The resulting civilization has been more successful – by orders of magnitude – than any other. Than any combination of others.

So why do we hear an endlessly-repeated nostrum that this wide-stance, mixed approach is all wrong? That mantra is pushed so relentlessly by right-wing media -- as well as some on the left -- that it came as no surprise when a recent Pew Poll showed distrust of government among Americans at an all-time high.

This general loathing collapses when citizens are asked which specific parts of government they’d shut down. It turns out that most of them like specific things their taxes pay for.

In a sense, this isn’t new. For a century and a half, followers of Karl Marx demanded that we amputate society’s right arm of market-competitive enterprise and rely only on socialist guided-allocation for economic control.

Meanwhile, Ayn Rand’s ilk led a throng of those proclaiming we must lop off our leftarm – forswearing any coordinated projects that look beyond the typical five year (nowadays more like one-year) commercial investment horizon.

Any sensible person would respond: “Hey I need both arms, so bugger off! Now let’s keep examining what each arm is good at, revising our knowledge of what each shouldn’t do.”

Does that sound too practical and moderate for this era? Our parents thought they had dealt with all this, proving decisively that calm negotiation, compromise and pragmatic mixed-solutions work best. They would be stunned to see that fanatical would-be amputators are back, in force, ranting nonsense.

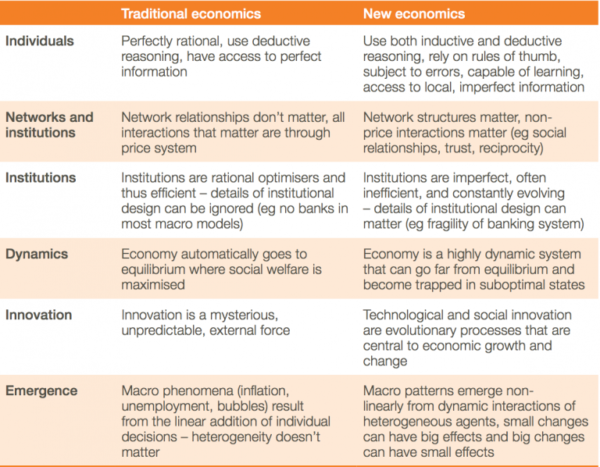

Take for example Matt Ridley’s recent article in the Wall Street Journal, deriding government supported science as useless and counter-productive— a stance dear to WSJ’s owner, Rupert Murdoch. Ridley’s core question - recently reiterated more concisely by Rep. Mick Mulvaney, Donald Trump's nominee as director of the Office of Management and Budget - is “Do we really need government-funded research at all?”

Ridley asserts that the forward march of technological innovation and discovery is fore-ordained, as if by natural law. That competitive markets will allocate funds to develop new products with vastly greater efficiency than government bureaucrats picking winners and losers. And that research without a clear, near-future economic return is both futile and unnecessary.

== The driver of innovation is… ==

Former Microsoft CTO and IP Impressario Nathan Myhrvold has written a powerful rebuttal to Ridley’s murdochian call for amputation. Says Myhrvold: “It’s natural for writers to want to come out with a contrarian piece that reverses all conventional wisdom, but it tends to work out better if the evidence one quotes is factually true. Alas Ridley’s evidence isn’t – his examples are all, so far as I can tell, either completely wrong, or at best selectively quoted. I also think his logic is wrong, and to be honest I don’t think much of the ideology that drives his argument either.” Nathan’s rebuttal can be found here, along with links to the original, and Ridley’s response.

Myhrvold does a good job tearing holes in Ridley’s assertion that patents and other IP do nothing to stimulate innovation and economic development. (Full disclosure: Nathan is more self-interested in fierce IP protection than I - a patent and copyright holder - am.) Only, in his refutation of Ridley, even he does not go far enough or present a wide enough perspective.

Myhrvold fails, for example, to put all of this intothe context of 6000 years of human history. So let me try.

During most of that time, independent innovation was actively suppressed by kings and lords and priests, fearing anything (except new armaments) that might upset the stable hierarchy. Moreover, innovators felt a strong incentive to keep any discoveries secret, lest competitors steal their advantage. As a result, many brilliant inventions were lost when the discoverers died. Examples abound, from Heron’s steam engines and Baghdad Batteries to Antikythera-style mechanical calculators and Damascus steel -- from clear glass lenses to obstetric forceps – all lost for millennia before being rediscovered after much unnecessary pain.

In his monograph: "Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive, and Destructive," William J. Baumol tells a story widely repeated among classical sources like Pliny and Petronius, of an inventor who presented the secret of unbreakable glass to Emperor Tiberius, only to receive death, instead of a reward, because the invention was viewed as destabilizing... a tale reset in China by Ray Bradbury in "The Flying Machine." Baumol cites earlier words by M. Finley:

"Technological progress, economic growth, productivity, even efficiency have not been significant goals since the beginning of time. So long as an acceptable life style could be maintained, however that was defined {by the ruling castes}, other values held the stage."

Those "other values" were critiqued by Adam Smith when he castigated the way oligarchs would rig markets to reward rent-seeking, noble privilege, monopolies, cartels or (in Baumol's more modern analysis) state corporations or organized crime. With rare exception, all such parasitical activities were more privileged than competitive innovation.

Staring across that vast wasteland of sixty feudal and futile centuries — comparing them to our own dazzling levels of inventive success, especially since World War II — slams a steep burden of proofupon someone like Ridley, who asserts we are the ones doing something wrong. Or that innovation zooms ahead as if by natural law.

== We are different. And different is difficult. ==

In fact, though well-nurtured and tended competitive markets are remarkably fecund, they are anything but “natural.” Show us historical examples! Kings, lords, priests and other cheaters always — always — warped and crushed market competition, far more than our modern, enlightenment states do. Indeed, Adam Smith’s call for a more “liberal” form of capitalism offered little ire toward socialists. His liberal approach calls on the state to counter-balance oligarchy, in order to keep capitalism flat-open-fair.

Our maligned democratic states — while imperfect and always in need of fine tuning — engendered revolutions in mass education, infrastructure and reliable law that unleashed creative millions, maximizing the raw number of eager competitors— exactly the great ingredient that Friedrich Hayek recommended and that Adam Smith prescribed for a healthy, competitive market economy.

To be clear, those who rail against 200,000 civil servants – closely watched, compartmentalized and accountable – “picking winners and losers” have a reasonable complaint! We are well-served by libertarians who point at this or that meddlesome excess. But not when their counter-prescription is handing over the same power to a far smaller cabal of 5,000 secretive and unaccountable members of a closed and incestuous oligarchic-CEO caste. Smith and Hayek both had harsh words for that ancient and utterly bankrupt approach.

(Question: who actually de-regulates, when appropriate? Democrats banished the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) when they were captured. AT&T was broken up, and the Internet was unleashed by Al Gore’s legislation. Add in Bill Clinton’s deregulation of GPS and Obama's declaration that citizens may record police... and one has to ask a simple question. Does anti-regulatory polemic matter more… or effective action? Despite their railings, 'conservatives' never deliver deregulation, except in two particular industries - finance and resource extraction - with historic results. Please name another example.)

Yes, history does offer us a few, rare examples in the past, when innovation flourished, leading to spectacular returns. In most such cases, state investment and focused R&D played a major role: from the great Chinese fleets of Admiral Cheng He, to impressive maritime research centers established by Prince Henry the Navigator that made little Portugal a giant on the world stage. Likewise, tiny Holland became a global leader, stimulated by its free-city universities. England advanced tech rapidly with endowed scientific chairs, state subsidies and prizes.

Those rare examples stand out from the general, dreary morass of feudal history. But none of them compare to the exponential growth unleashed by late-20th Century America’s synergy of government, enterprise and unleashed individual competitiveness, the very thing that all those kings and priests and lords used to crush, on sight. One result was the first society ever in the shape of a diamond, instead of the classic, feudal pyramid of privilege – a diamond whose vast and healthy and well-educated middle class has proved to be the generator of nearly all of our great accomplishments.

It is this historical perspective that seems so lacking in today’s shallow political and philosophical debates. It reveals that the agenda of folks like Matt Ridley, Mick Mulvaney, or Rupert Murdoch is not what they claim -- to release us from thralldom to shortsighted, oppressive civil servants and snooty scientist-boffins.

Their aim is to discredit all of the modern expert castes that we have established, who serve to counterbalance (as Adam Smith prescribed) the feudal pyramids under which our ancestors sweltered in constraint. Their aim is a return to those ancient, horrid ways.

== Before our very eyes ==

I believe one of our problems is that the Rooseveltean reforms – which historians credit with saving western capitalism by vesting the working class with a large stake, something Marx never expected – were too successful, in a way. So successful that the very idea of class war seems not even to occur to American boomers. This despite the fact that class conflict was rampant across almost every other nation and time. But as boomers age-out is that grand time of naïve expectation over?

To a restoration of humanity’s normal, aristocratic pyramid of power, with them staying on top?

Or to radicalization, as a billion members of the hard-pressed but highly skilled and tech-empowered middle class rediscover class struggle?

== We've been here before ==

The last time this happened, in the 1930s, lordly owner castes in Germany, Japan, Britain and the U.S. used mass media they owned to stir populist rightwing movements that might help suppress activity on the left. Not one of these efforts succeeded. In Germany and Japan, the monsters they created rose up and took over, leading to immense pain for all and eventual loss of most of that oligarchic wealth.

In Britain and the U.S., 1930s reactionary fomenters dragged us very close to the same path… till moderate reformers did what Marx deemed impossible – adjusted the wealth imbalance and reduced cheating advantages so that a rational and flat-open-fair capitalism would be moderated by rules and investments to stimulate a burgeoning middle class, without even slightly damaging the Smithian incentives to get rich through delivery of innovative goods and services.

That brilliant, positive-sum moderation led to the middle class booms of the 50s and 60s and – as I cannot repeat too often - it also feature big majorities in our parents’ Greatest Generation adoring one living human above all others: Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

(Pose the question to your "make America Great again" neighbors: "When was America great?" Then remind them who the GGs loved.)

Some billionaires aren’t shortsighted fools, ignorant of the lessons of history. Bill Gates, Warren Buffet and many tech moguls want wealth disparities brought down through reasonable, negotiated Rooseveltean-style reform that will still leave them standing as very, very wealthy men. Heck, even Glenn Beck can see where it all leads, declaring (in effect) "OMG what have I done?"

The smart ones know where current trends will otherwise lead. To revolution and confiscation. Picture the probabilities, when the world’s poorest realize they could double their net wealth, just by transferring title from 50 men. In that case, amid a standoff between fifty oligarchs and three billion poor, it is the skilled middle and upper-middle classes who’ll be the ones deciding civilization’s course. And who do you think those billion tech-savvy professionals – so derided and maligned by murdochian propaganda -- will side with, when push comes to shove?

== Back to innovation ==

Oh, for an easy-quick and devastating answer to the “hate-all-government” hypnosis! How I'd love to see a second "National Debt Clock" showing where the U.S. deficit would be now, if we (citizens) had charged just a 5% royalty on the fruits of U.S. federal research. We'd be in the black! How effective such a “clock” would be. We deserve such a tasty piece of counter propaganda. (See: Eight Causes of the Deficit Fiscal Cliff.)

Closer to the point, consider this core question: how have we Americans been able to afford the endless trade deficits that propel world development? (And make no mistake; 2/3 of the planet developed - sending their kids to school - in one way only: by selling Americans trillions of dollars worth of crap we never needed.)

How did we afford this flood of stimulating red ink for 70 years?

Simple. Science and technology. Each decade since the 1940s saw new, U.S.-led advances that engendered enough wealth to let us pay for all the stuff pouring out of Asian factories, giving poor workers jobs and hope. Our trick was to keep the wonders coming -- jet planes, rockets, satellites, electronics & transistors & lasers, telecom, pharmaceuticals... and the Internet.

Crucially, the world needs America to keep buying, so that factories can hum and workers send their kids to school, so those kids can then demand labor and environmental laws and all that. The job of George Marshall’s brilliant trade-policy plan is only half finished. Crucially, the world cannot afford for the U.S. consumer to become too poor to buy crap.

Which means we must protect the goose that lays golden eggs – our brilliant inventiveness. Our ability to keep benefiting from enlightenment methods that stimulate creativity. And that will not happen if the fruits of creativity are immediately stolen. There is a bargain implicit in today’s rising world. Let America benefit from innovation, and we’ll buy whatever you produce.

Foreign leaders who ignore that bargain, seeking to eat the goose, as well as its eggs, only prove their own short-sighted foolishness… like our home-grown fools who rail against all government investment and research.

It is time to have another look at the most successful social compact ever created – the Rooseveltean deal made by the Greatest Generation, which we then amended and improved by reducing race and gender injustice and discovering the importance of planetary care.

Throw in a vibrantly confident wave of tech-savvy youth, and that is how we can all move forward. Away from dismal feudalism. Toward (maybe) something like Star Trek.